History

Origins of Friends of Deckers Creek

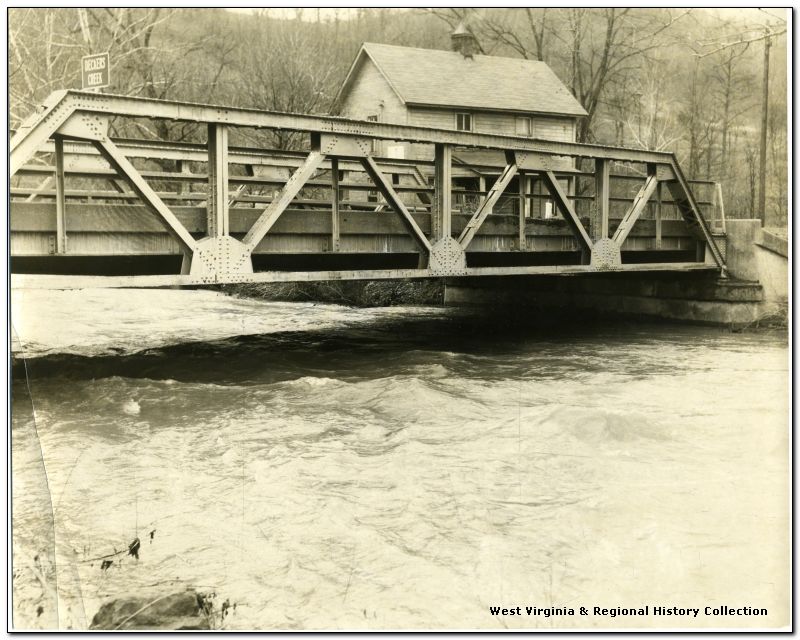

In 1995, Friends of Deckers Creek (FODC) was started with the thought that Deckers Creek was beautiful, wild, and terribly mistreated. Upon seeing a need for change, an informal group of kayakers, rock climbers, anglers, and other creek enthusiasts started organizing clean-ups of illegal dumps and monitoring the creek's water quality. By 1997, this group began receiving small grants to support their work. FODC then obtained 501(c)(3) nonprofit status in 2000 and held its first membership drive in 2001.

In 1998, the state Department of Environmental Protection and federal Natural Resources Conservation Service committed $10 million to clean up acid mine drainage in the Deckers Creek watershed, an effort that continues to be guided by FODC even now.

The dedication of our founders is what made this whole organization possible. We are very lucky to have had these people planting the seeds of Friends of Deckers Creek, absolutely improving our community and our wildlife ecology for years afterwards.

Discovering Deckers Creek

Native American tribes occupied the lands of the Monongahela from about 8000 B.C. to about 1700 A.D. Shawnee, Mingo, Delaware, and many other tribes lived here and used the bountiful wildlife for hunting, gathering, and shelter. The name "Monongahela" means "the river of falling banks" in Lenape, a language of the Delaware tribe.

Deckers Creek is a tributary of the Monongahela River flowing from Preston County into Monongalia County, West Virginia. Although native tribes have lived and worked this region for thousands of years, the stream is named for the European family that settled at its mouth in the spring of 1758. In the colony were brothers Tobias (or Thomas), Garrett, and John Decker, their families, and at least 19 other adults and numerous children.

Below are some accounts by local historians.

The small colony was attacked in 1759 by a party of about 30 marauding Delaware Indians who killed eight of the settlers, destroyed their livestock, harvested their crops, and burned their cabins. Although 39 people escaped the carnage and the settlement apparently disbanded after the violence, the stream became known as Deckers Creek.

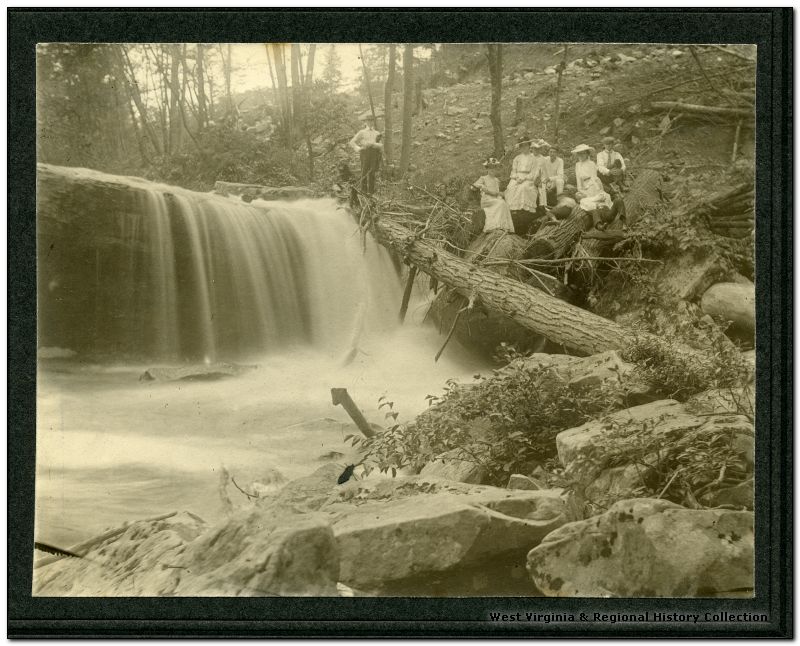

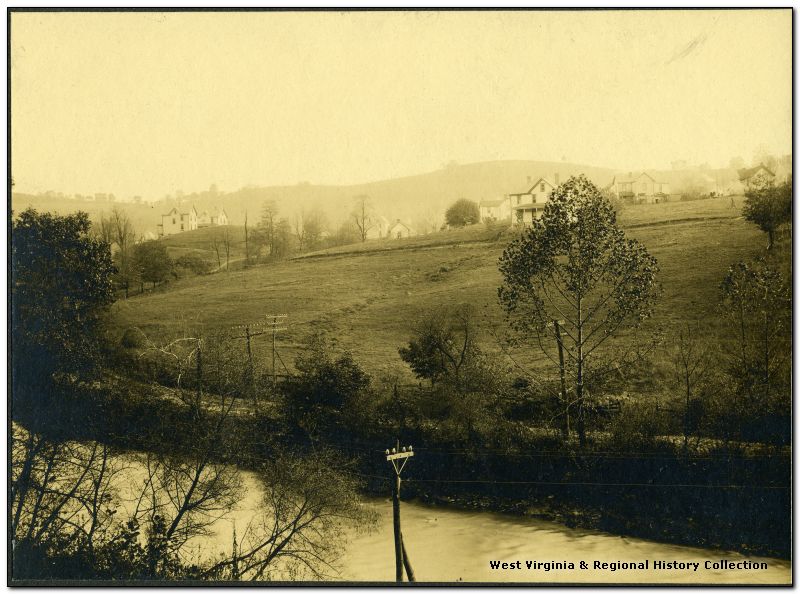

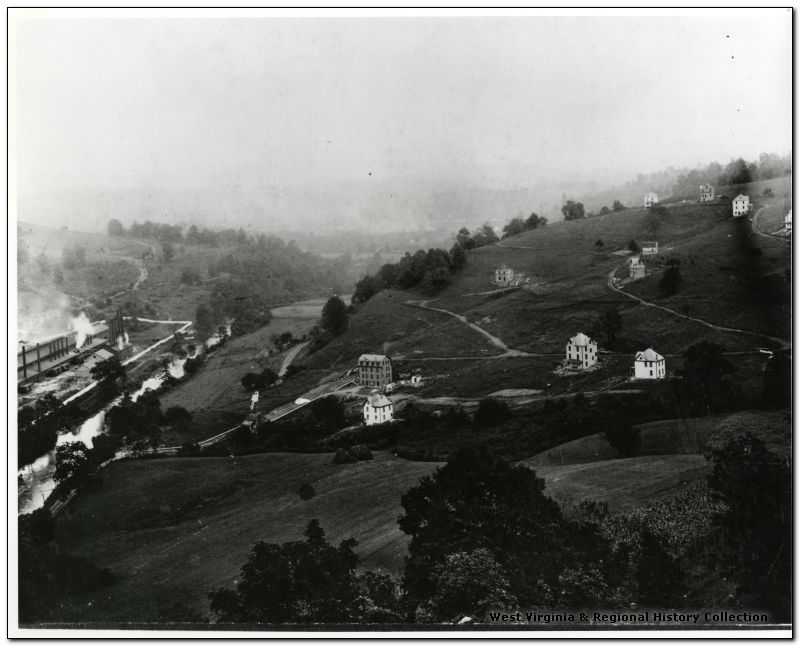

By the 1760s European settlers returned to lower Deckers Creek near present-day Morgantown. The creek’s importance to Morgantown was evident from the beginning, as economic growth came from industries that used the creek as a source of water power for a forge and iron furnace, grist (grain) mills, saw mills, and a pottery and a paper mill. These early enterprises signaled the beginning of industry in the Deckers Creek valley.

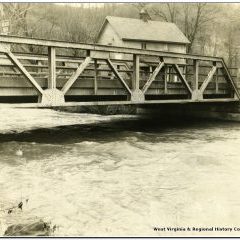

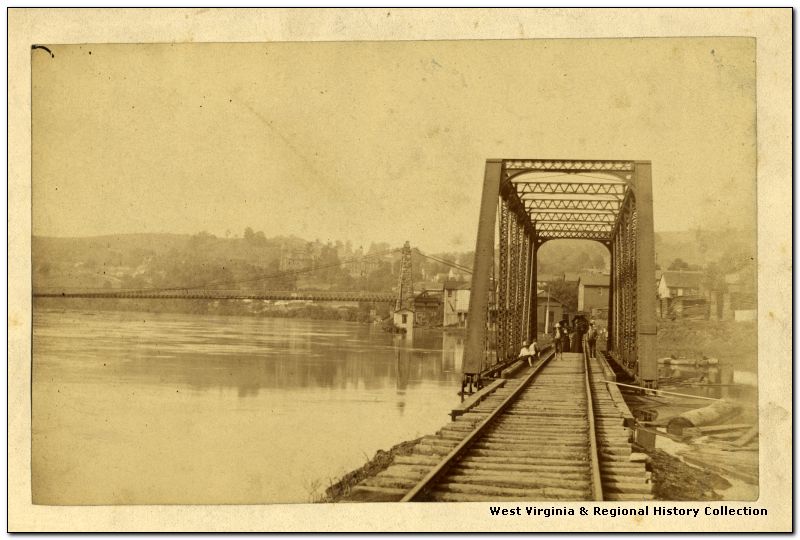

In 1886 the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad reached Morgantown along the Monongahela River. This opened up the sleepy college hamlet and fueled area development. After several false starts, industrialist George Sturgiss led the effort in 1899 to build the Morgantown and Kingwood Railroad up Deckers Creek.

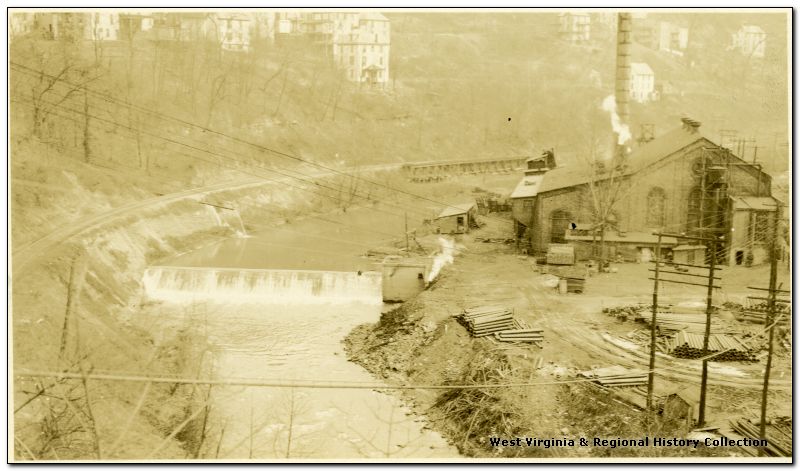

This line reached Masontown by 1902 and the area's rich reserves of timber, coal, and limestone began to be harvested. Within a relatively short time, mines, quarries, and coke ovens dominated the landscape of the Deckers Creek valley from Reedsville to Rock Forge. In 1903 a tin plate mill opened in Sabraton and a large modern electric plant was built along the creek in Morgantown.

Rapid industrialization in the first half of the 20th century took a heavy toll on the once-pristine Deckers Creek, as water quality declined and aquatic life diminished. Recreational fishing and boating on the creek eventually ceased after acid mine runoff and open sewage fouled the water.

Conditions got so bad by 1935 that Morgantown city officials were warned by the state health department to clear the stream of sanitary waste. But by then lower Deckers Creek was terminally ill from the ravages of uncontrolled development: by the time the creek reached Morgantown the contamination killed it.

In the late 1930s Morgantown realized it needed an interceptor sewer along Deckers Creek. After waiting 25 years due to a shortage of funds, the sewer was completed in 1962. Although this eliminated odors emanating from the lower reaches of the stream, mine acid and raw sewage still entered the watershed from points upstream. By 1964 the Morgantown Sanitary Board was created with the responsibility of building and maintaining a sewage disposal system.

While much progress has been made in the last two decades to clean up the creek, much remains to be done. Fortunately, Deckers Creek has been rediscovered by a hardy group of outdoor enthusiasts and area residents who refuse to accept the notion that the stream is beyond repair. Like the European settlers and the native Americans before them, area residents are once again looking to Deckers Creek for opportunities, only this time the motivating factor is recreational development.

But first we must reverse the ravages of the last 100 years and change the indifferent attitude that has evolved over time. We must learn to regard the stream as a living component of the culture and history of Preston and Monongalia counties, and not merely as an open dump or a convenient outlet for human and industrial waste.

Friends of Deckers Creek is committed to reversing the sad plight of Deckers Creek and making sure that history does not repeat itself in the 21st century.

The Decker family arrived in New Amsterdam with the patriarch Johannes de Decker as supercargo on the ship Black Eagle in April 1655. As the western frontier was opening up the Decker family moved west with Abraham Decker founding Monongahela City, PA. Gerrit, Tobias, Thomas, and other traveled into the South Branch Potomac River area and started farming.

In May, 1757 Reuben Cox; the brothers Garret and Tobias Decker, David Morgan, Nathaniel Springer, John Ice, Henry Falls, Samuel Bingaman, and others trailed about twenty Indians and two Frenchmen from the South Branch of the Potomac River — where these Indians had murdered six white men and carried off another, George Delay — across the Allegheny Mountains and onto the Cheat River, where they overtook and skirmished with them, killing seven Indians and one Frenchman. This happened about five or six miles above where the Ice family kept a ferry.

Delay was wounded and died of his injuries while being carried across the mountains. Cox and Morgan, among others, pursued the fleeing French and Indians to Bingaman Creek, on the West Fork River. Here they lost the enemy's trail. David Morgan, Nathaniel Springer, Cox and the others camped for about two weeks at the mouth of Deckers Creek.

During this time, they hunted, gathered ginseng, and explored the Deckers Creek valley. They found documents on the French soldier ordering the attacks on the English settlements. They then returned home to the South Branch valley.

Thomas Decker was the first to settle in the area of Deckers Creek and the Monongahela River in 1758. Others in the settlement were brothers Tobias, Garrett, and John, and their wives and children; the Deckers’ brother-in-law William Zern, wife and children; Garrett Decker’s son in law Richard Falls, wife and son Robert Falls; the Thorn brothers, Tobias, Henry, and Lazarus, their wives and children and their stepmother and her son, Michael, aged about two years; her brother-in-law, William Westfall, his brother, Abel, their wives and children; Reuben Cox and his ten-year-old son, George Cox; and a single man, John Statler.

The settlement was destroyed on the afternoon of 16 October 1759. The settlement was attacked by about 30 Delaware and Mingo Indians. Of the original settlers, eight people and their livestock were killed, including Thomas Decker, and their cabins and crops were burned and destroyed. Many were captured in the attack. The survivors relocated near the area of the Ice family’s ferry on the Cheat River, which later became an important shipping site.

In 1758 Richard Falls and others marked off claims, cleared land, raised cabins, and planted crops near Deckers Creek. Richard Falls became a settler in the Monongahela valley, claiming 400 acres in 1760. Richard served during the French and Indian war. Henry and Richard Falls also fought for the PA line. Henry’s unit was the 10th Reg, Continental Line with Robert Samjle’s Co. Henry was also a Private in the 5th Co. with Capt. Jason Long. Richard was a private in the war for three years PA Line, 8th Reg, Capt. Thomas Coats’ Co.

In 1766 David Morgan gave his settlement rights to his brother Col. Zackquill Morgan, who later established Morgantown in 1782 as the county seat on the site of the original Thomas Decker settlement.

The Monongahela River was an important shipping avenue to the Ohio River and then the Mississippi River, which is how the Falls and Deckers migrated to other areas. Tobias Decker relocated on 8 September 1778 to Youghiogeny County, Virginia. Richard Falls' son Robert eventually married Anna Severns and settled in Gibson Co. Indiana, having several more kids and eventually me.

[ It may be noted that a reader of our Web site and genealogical researcher has questioned the certainty of Robert Falls being son of Richard Falls. We have not investigated the evidence. ]

History of the Monongahela River

From the Upper Mon Trail brochure:

The Monongahela River formed some 20 million years ago. Because of a series of 9 Locks and Dams, the Mon today is deep enough for tow boats with barges to navigate. The dams maintain at least a 9-foot channel for boats. In its natural state, though, the river was much more shallow.

In fact, when the first pioneers saw the Mon, they may have been able to walk across it. Native Americans occupied the lands of the Monongahela from about 8000 B.C. to about 1700 A.D. Shawnee, Mingo, and other tribes claimed and used the region as a hunting ground. The Native Americans named the river Monongahela, which is said to mean "river with crumbling or falling banks."

Indian traders and pioneers from colonial settlements came to the Upper Mon as early as 1694, when a small temporary settlement was made near present-day Rivesville. Hostile tribes destroyed attempts at permanent settlements, such as those at Dunkard's Creek (1757) and Decker's Creek (1758). The first permanent settlements came shortly after the close of the French and Indian War (1763), but forts were still necessary for protection. Pricketts Fort, just north of Rivesville and accessible from the Mon, is a reconstruction of such a fort.

Navigation on the river began with canoes and bateaux, but as settlements along the Mon grew, pioneers needed a means to send goods down-river to Pittsburgh and ports in the south. At first, they built flatboats, which could only go down river. Later, keelboats were built. These vessels traveled both down and up river. Old Monongahela Rye Whiskey was one of the area's principal early agricultural products exported by way of the Mon using flatboats and keelboats. In 1811, the steamboat New Orleans was launched on the Mon at Pittsburgh, and made the first trip to New Orleans.

In the 1840's, locks were built on the Lower Mon in Pennsylvania, and by 1904 the Corps of Engineers completed five additional locks and dams in West Virginia, making the Mon the first American river slack-watered its complete length. Remnants of early locks can be seen at various locations.

Throughout the years, tow boats have transported coal barges filled with millions of tons of cargo for the steel mills in Pittsburgh, power plants along the Ohio River, and on to New Orleans for international distribution. The imprint of King Coal has been left with acid-mine drainage that has flowed from mines for years. Cultural aspects of mining are evident. Active and abandoned coal loading docks may be seen from the river. Since implementation of the Clean Water Act in 1972, the waters of the Mon have become cleaner, with communities focusing their gateway development to include riverfront parks.

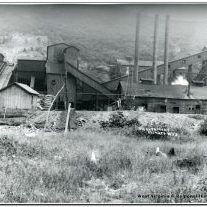

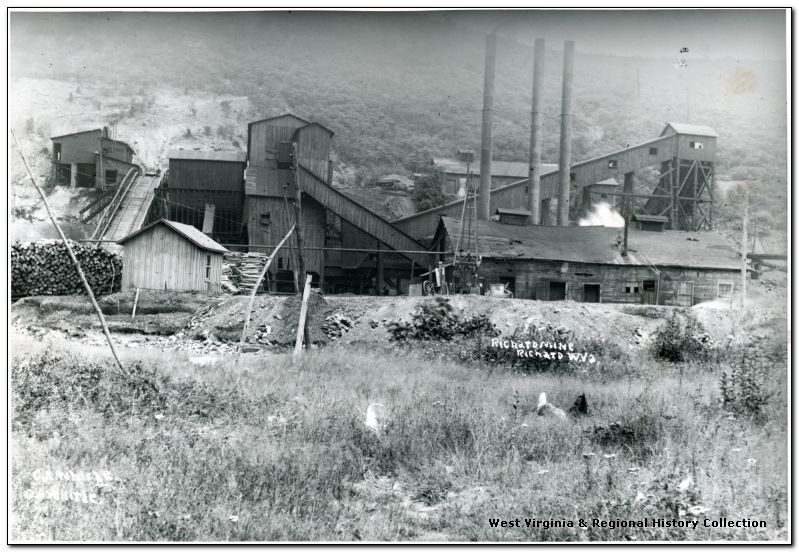

History of the Richard Mine

The mine which was to be become the Richard Mine was first established in 1903 by the West Virginia Coal Company to fuel 75 beehive coke ovens already in existence at the site. During the following three years, Stephen B. Elkins acquired the mine and its coke ovens adding to his already massive holdings with the Elkins Coal and Coke Company. The coal camp of Richard was then created and named for Elkins’ son. The settlement soon developed a reputation for it's clean and tidy appearance and quality of life.

Stephen B. Elkins served as a Senator from West Virginia as well as Secretary of War under President Benjamin Harrison. Elkins, a Republican, married the daughter of Henry Gassaway Davis, a Democratic Senator from West Virginia and together they partnered in many business interests including rail-roads and coal mines. Eventually, Davis and Elkins College would be named for the duo.

Elkins was also buying large tracts of coal and bringing them into his company’s holdings. In 1902, Elkins purchased the uncompleted Morgantown and Kingwood Railroad. The modern Deckers Creek Rail-Trail follows the original path of this railroad. The Morgantown and Kingwood Railroad connected to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroads which brought the majority of the coal and coke produced in the area east to the steel mills at the Sparrow’s Point Complex outside of Baltimore. The Bethlehem Steel Corporation in 1914 purchased Sparrow’s Point and eventually came to own the Elkins holdings as well.

In 1919, the Penn-Mary Company acquired the Richard Mine, which was a subsidiary of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation at the time, having been acquired in1916. In the West Virginia Department of Mines Annual Reports the Richard Mine is listed as Penn-Mary No. 21 from 1919 to 1921. The listing of the Richard Mine in the annual reports continues every year under ownership of Bethlehem Mines Corporation until 1929 when Bethlehem Mine No. 21 no longer appears in the records under Monongalia County.

After an absence of 7 years, the Richard Mine reappears in 1936 as Industrial Collieries Corp No. 21, another subsidiary company of Bethlehem Steel. The records show that the mine operated under ownership of Bethlehem Steel until it closed in 1952. During the mine’s second operational phase the most active year was 1942, with the mine employing over 500 people and producing over 600,000 tons of coal.

Coke was a fuel derived from coal and used in the steel making process by the mills, which were typically located on the East Coast. To produce coke, a base fuel such as coal or wood is burned with a shortage of oxygen (air) at extreme temperatures until pure carbon remains.

The coke is then doused with water to cool it before being transported. Pure carbon is critical to the iron and steel making process as it is used to extract oxygen from iron ore creating a pure metal. The use of coke originated in 18th century Britain and was practiced widely in the United States using charcoal and anthracite coal as fuel. As a temperature control measure, British coke producers developed the round top ovens which resembled beehives and lead to the name of the design.

Coke production first began to rapidly increase in the time immediately after the American Civil War as the demand for iron and steel increased rapidly due to the rail road industry. The United States was to become the largest producer of steel in the world during this era and beehive coke ovens provided the majority of the fuel for the blasting furnaces up until 1919. After World-War I, by-product ovens were created and implemented to recover gases and chemicals from the coal coking process. Beehives were rendered obsolete and Bethlehem Steel moved coking operations to a by-product facility at Sparrows Point in Maryland.

The Sparrows Point Steel Mill grew to employ over 30,000 people and was the largest steel mill in the world during the 1950s. The Sparrows Point Steel Mill was also instrumental in the American war effort during the 1940s. Producing 116 ships between 1939 and 1945, mostly tankers and cargo vessels. The Richard Mine also had the highest amount of production in those years. Bethlehem Steel went bankrupt in 2003 and the Sparrow’s Point facility officially closed in 2012.

Other sites in the area including Bretz continued to produce coke in traditional beehive ovens as late as the 1980s. The facility at Bretz was also originally owned by Elkins Coal and Coke Company and later Bethlehem Steel and was situated on the same railroad as Richard. There have been verbal reports that the Beehive ovens at Richard operated in the years after the mine closed.

The area has since been returned to a mixed-use residential and commercial space, especially through the unincorporated community of Richard. The building currently housing United Janitorial Supply was the company store for the coal camp of Richard. The company office building is also still standing, which served as a school house in the years after the mine was closed. That building serves as a private commercial building to this day.